Jack Guy, our Fellow at Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, tells the little-known story of Henry William Hunt, a pioneering 19th century disabled artist.

Henry William Hunt’s early years

Henry William Hunt, although not well known today, was a pioneer in the use of watercolour and an influential figure in British fine art scene in the 19th century. Hunt was born in 1790 at 8 Old Belton St, Holborn, London, to Judith and John Hunt. John Hunt was a self-employed tinman creating tin lighting for theatres, and a japanner varnishing decorative tin wear. Henry was born with physical disabilities seeing him develop a small statue of a “little less than…five foot”. He also had a large head and shoulders compared to the rest of his body and turned in toes and knees, limiting his mobility.

These physical disabilities saw many around him, including his uncle, see him only as a “poor cripple” that “was not fit for nothing”. However, his disabilities did not hold him back and gave him a perspective that others could not see. His vision and flair for art eventually saw his father support him, paying £200 for Henry to become an apprentice to the watercolourist John Varley in 1806.

Henry learnt a lot from John Varley, especially the method of the ‘academy of nature’ where the artist critically observed his surroundings and portrayed them as accurately as possible – a style that is present through all of Hunt’s work. Whilst being an apprentice for seven years, Hunt developed quickly, exhibiting several times at the Royal Academy, his first being when he was only 17 years old. Varley’s teaching not only helped Hunt to progress his artistic styles but also introduced him into influential circles of patrons, such as the Duke of Devonshire, the Earl of Essex and Dr Monro.

Hunt’s isolation within society

These introductions were important to Hunt as he was “reserved” to strangers and struggled to participate in formal social activities. This was not only due to his social background, being the son of a craftsman, but also because of contemporary attitudes towards disability. Even his friend Ann Merry Wood who would speak of him fondly as having the “tenderest heart”, also viewed Hunt as a “Quilp (grotesque) like dwarf”.

Unfortunately, this social removal saw Hunt develop an extreme dislike of his appearance. G.P. Boyce noted in his diary that “W.H Hunt had a morbid conviction of his own ugliness and desired that all records of him to the present in the way of portraits and letter should be destroyed”.

This remoteness he experienced within society transferred into how William Hunt created his artwork. For example, where other artists often use different models, Hunt relied on those he had a personal connection with, including his wife Sarah and daughter Emma. By knowing the sitter intimately, Hunt was more at ease and better able to capture the individual’s character, making his portraiture immeasurably expressive and personal.

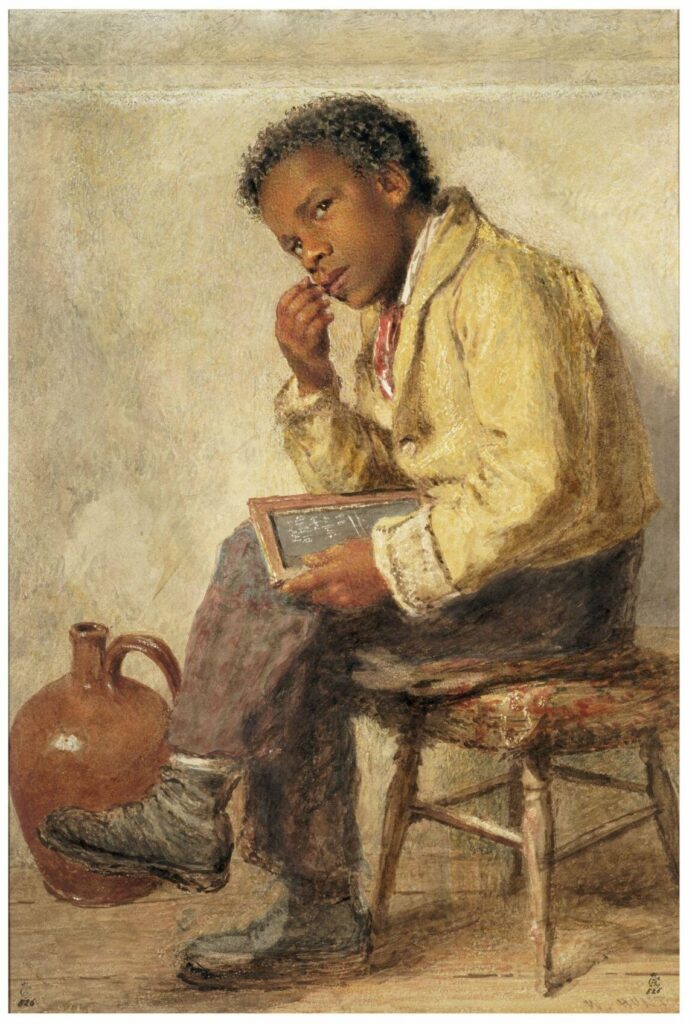

The marginalisation that Hunt experienced also gave him inherent sympathy for others who had experienced the same treatment. As highlighted by one of his early biographers, “he [Hunt] was addicted to low company, and street conjurers, acrobats and [black performers] were always welcome at his tea table of his humble lodgings”. Hunt often painted many of his friends who sat at his table, seeing his work depict another side to Victorian London society that is not often seen in portraits of the time.

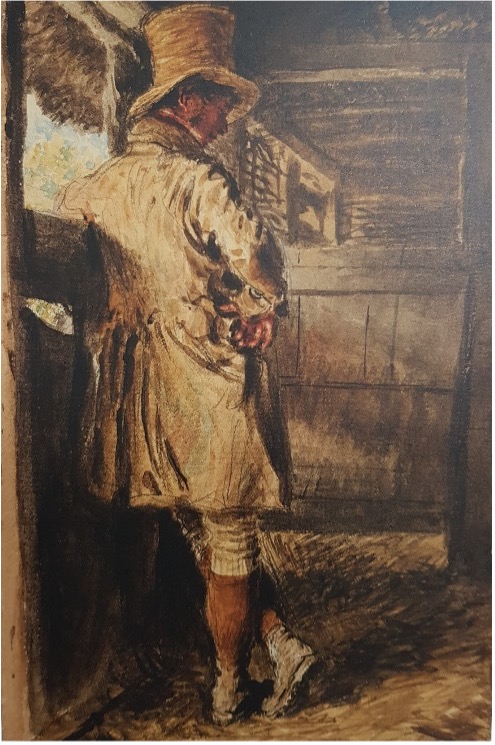

Hunt’s disability also influenced how he depicted the world around him. As he had to sit down when painting for long periods of time, the composition of his portraits altered. This is most notably seen in The Farmer in the Barn (1820). In this piece, Hunt sits behind the farmer, seeing the figure stand with an added air of control and confidence in the painting. In other works, such as ‘The Attack’ (1834), Hunt is seated at the same height as the boy, making the painting more personal and drawing us into the struggle of the boy cutting the pie.

Developing a unique artistic style

Hunt’s artistic style was not only influenced by his disability and social marginalisation but also by his passion, vision, and dedication to watercolours. He continuously developed his style over the decades, evolving what he had learnt from Varley and others. Within ten years of leaving Varley’s apprenticeship, he was using large quantities of opaque white, stippled watercolour, translucent washes, minute brushstrokes and large areas of scratching in his work. These techniques would later be used prominently by the Pre-Raphaelites.

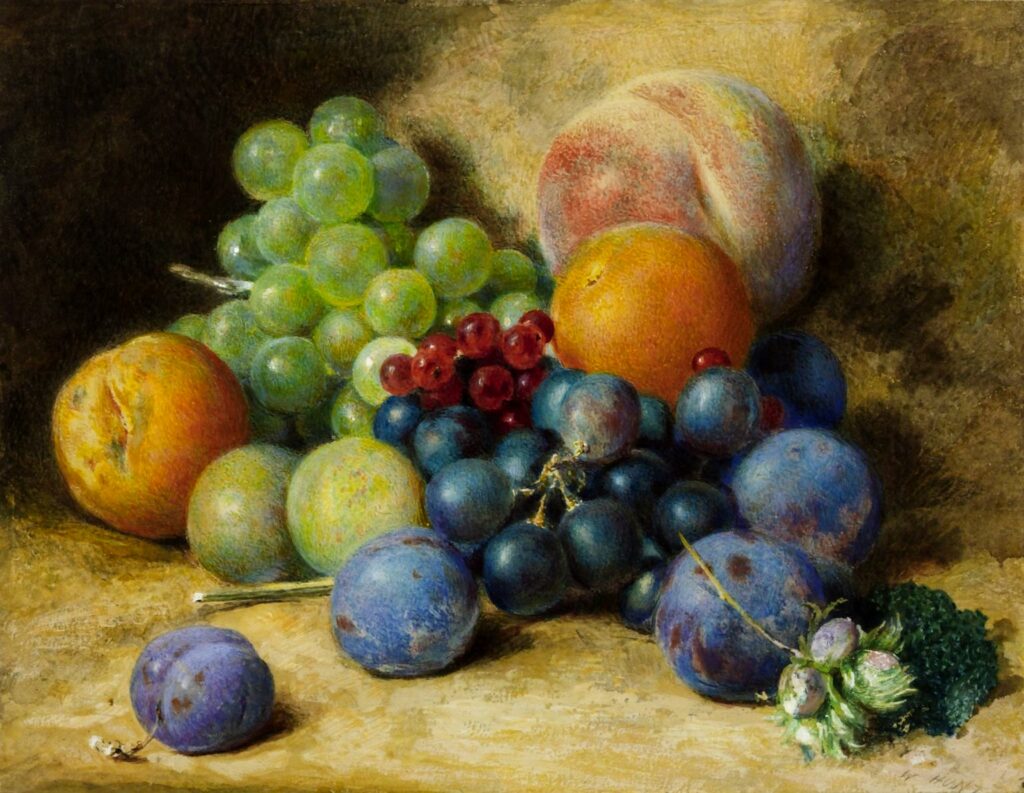

Hunt’s development of watercolour was not only in evolving techniques but also in effectively creating two genres. The first being naturalistic still lifes, depicting mainly fruit in great detail, and the second is single comic figures, such as the painting ‘The Attack’ and its sister painting ‘The Defeat’. These developments within the medium of watercolour painting not only added new categories but also saw colour, contrast and expression placed at the centre of the work.

His ability to depict life in such detail and capture caricature models made him an exceptional artist that even his contemporaries, such as Richard Redgrave, praised. “The works of Hunt differ widely from his contemporaries: they have a character of their own and many qualities which place him as an artist, in his somewhat narrow range, on a level with the highest”.

Hunt continued to paint and teach until his death on the 10th of February, 1864, after a sudden stroke at the age of 74. Although Hunt is “perhaps one the most neglected and under-documented watercolourists of the 19th-century”, his ability to paint in such detail and express such emotion and charm see that his story will not be forgotten. The boy that was “fit for nothing” will be remembered as one of the most influential artists of his day.

Work by Henry William Hunt appears in the Curating for Change exhibition Stored Out of Sight: Hidden History of Disabled People at Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, curated by Jack Guy.