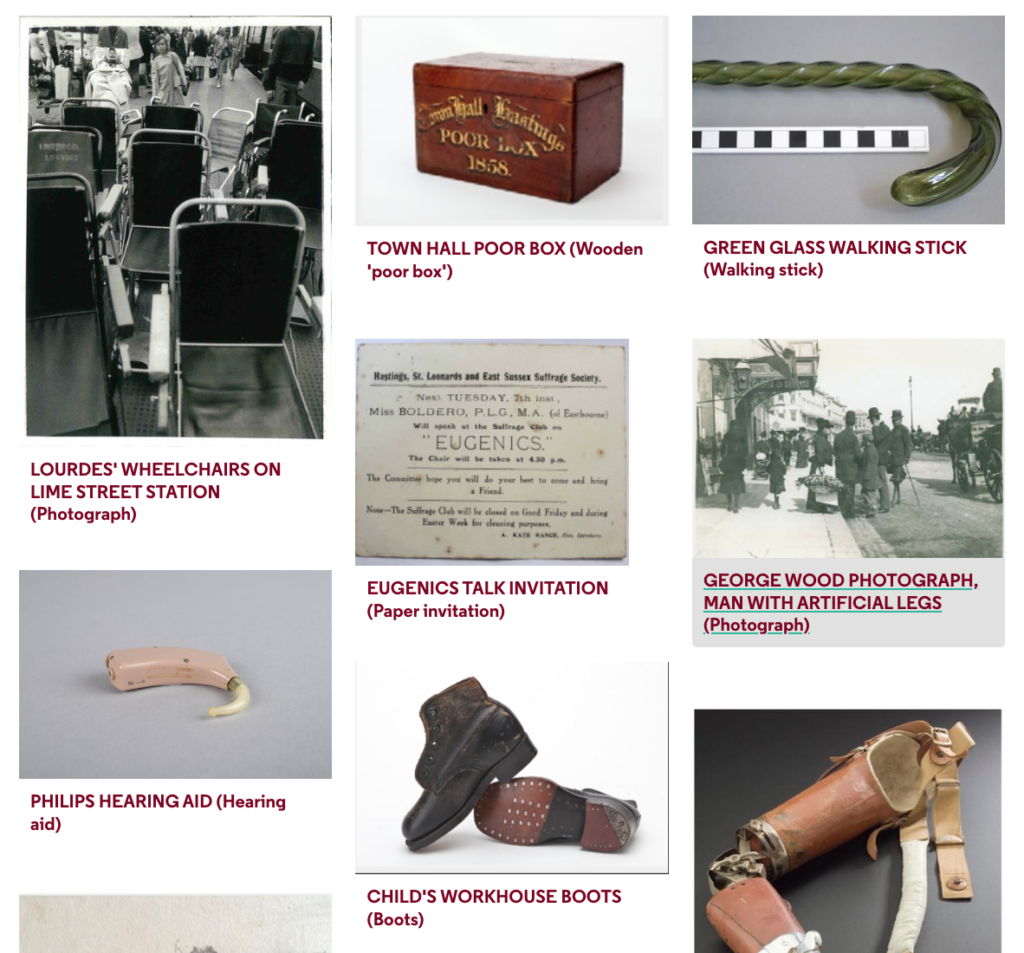

Curating for Change has twin aims – to create career paths for D/deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people in museums, and to discover and share disability histories. Over the last 18 months, our Fellows and Trainees have been delving into museum stores, sifting through catalogues and working with disabled people in their local communities to uncover untold disability stories.

We are now starting to share these discoveries online, through our Collections database. Our aim is to do something unique with this database – to bring together and celebrate disability stories from museums across the country, create a tool which will enable the public to discover them, as well as offering a valuable research resource. Working with our Fellows and Trainees, as well as our web partner Museum Platform, we have been exploring the best way to share these collections.

What counts as disability history?

Whilst we are sharing assistive objects such as walking sticks and hearing aids, we wanted to broaden the sense of what can be considered disability history. It was also important to (wherever possible) focus on the stories of people, rather than just objects, or that we considered the way people might have responded to or used objects.

For this reason, the items in our collections may not have an immediately obvious connection to disability, but they might represent an owner who had a disability story. Other items may have been a source of discussion or inspiration for the disability history groups that our Fellows and Trainees are working with. Some Fellows and Trainees found it challenging to find collections with a direct connection to disability, so instead found ways to react to or reinterpret the broader collections, or call out for additional items to be added from the community. Most importantly, we have focused on items which our Fellows, Trainees and communities feel passionate about, or feel represent something significant or important within their museums’ collection.

How should we talk about disability in this Database?

Once thinking about putting these items into a database, the next question was how to represent and talk about disability, in a way that is inclusive but also useful for searching. An exciting opportunity of the database is the ability to create new connections between museum collections across the country, but to do this we needed to be able to categorise items by specific impairments or conditions. However, our project is informed by the social model of disability, in which the focus is on the ways that society disables people, rather than the medical model, which focuses on specifics of conditions or impairments. So, we had some concerns about using medical terms to categorise items.

We concluded that we should categorise items by a specific impairment, condition, or experience if we felt it was relevant to that item (such as a hearing aid), or if our Fellows, Trainees or community co-producers felt it was important to do so (for example, someone wanting to talk specifically about their experience of Down’s Syndrome). We came up with a top level list of categories of impairment, experience or condition, such as chronic illness, visual impairment, and neurodivergence, and in general avoided medical terms or specific conditions. But we also gave our Fellows and Trainees the option of adding additional keywords, conditions or terms if they wanted to.

Language around disability was also important to consider, as this is a changing picture, and some of the historic items we are working with may use language now considered derogatory or offensive. We didn’t want to cover this up, and indeed some of our Fellows and Trainees were interested in focusing on these items. We concluded that these could be used within the description of item, when interpreted and contextualised.

How should you categorise objects in a Database?

A key challenge for creating a database of this kind is that we are working with museums of all sizes, in many different locations, with collections ranging from contemporary photographs to videos of dance performances to ancient Egyptian objects. To categorise these items, we decided to provide a wide range of optional fields for Fellows and Trainees to complete, as well as a number of compulsory fields which would mean users could filter the entire database. These were museum; impairment, condition or experience; time period and country (although it is possible to select ‘unknown’ or ‘not applicable’ if any of these are not possible to complete). We also left the potential to create some additional fields, if we encounter information that doesn’t have a natural home.

Perhaps the most important element of the database, however, is the ‘description’ field, where our Curating for Change Fellows and Trainees can describe the item, add their own interpretation, and add community curation from their disability heritage co-production groups. Through Museum Platform we also have the capability to add more rich content such as galleries, 3D renderings and videos, so we can continue to enhance these records as they are explored and interpreted.

How can a Database be accessible?

Accessibility is obviously a particular focus for our project. We aim to start each item description with a visual description of the item. We make any text as clear and simple as possible. And any video content will be subtitled and if we are filming content we include BSL interpretation. But we’re always keen to have any feedback on how we can improve accessibility. In future we would like to expand the database beyond these museums, and possibly open it up to the public to submit collections which they feel are important.

This is a new undertaking, and we are learning all the time. So if you have feedback on the language we use, or ideas for collections which could be added to our database, please get in touch at [email protected]

Blog credit: Melissa Boxall